<aside> ☝ I’ve long been a believer that if you are going to take a negative view of something you ought to have a positive suggestion to put in its place. This blog post is a companion piece to Against Worldviews. It outlines my view of a subject that is fit-for-purpose.

</aside>

Table of Contents

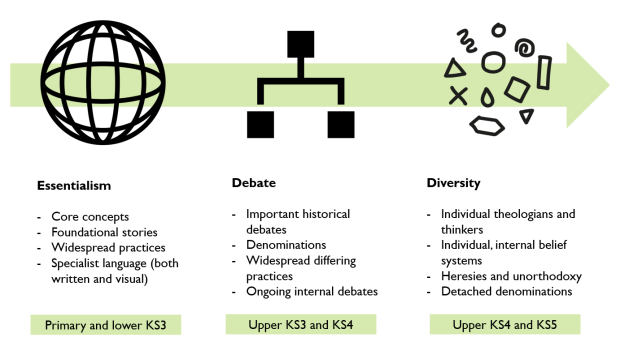

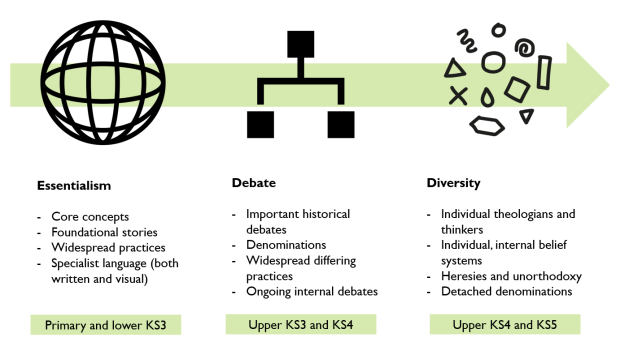

There has been much debate about what progression looks like in RE. To my mind the inability to agree on a model of progression over time is linked to two developments within RE, one is the prevalence of thematic study which does not lend itself to a straightforward model of progression and the second is a fear of essentialism that makes the early stages of such a model very hard to theorise.

I can sympathise with the fear of essentialism. As RE teachers we want to feel as though we are representing religions as diverse and colourful bodies of belief and practice and not as single monolithic institutions to which followers pay absolute obedience. However, as Neil McKain so rightly describes in his chapter In defence of essentialism, in the book Reforming RE, “to essentialise is to simplify so as to enable understanding. Students should be made aware of diversity but only after we have taught them the basics” (p.194).

All subjects essentialise, this is certainly something I am certainly having to learn as a primary school teacher. RE, however, is not essentialising something distant like the causes of WWII or abstract like how to calculate the area of a triangle, it is essentialising belief systems that we ourselves, or our students, or people we know and respect, hold in a very real and earnest way. I recall a lecture on my PGCE from a member of a faith community who told us in no uncertain terms that to refer to their place of worship as the “x version of a church” or to compare their holy book to the Bible was a huge faux pas. I then remember talking to my fellow student teachers weeks later and sharing embarrassing stories of how we’d frozen in the classroom remembering this lecture and being unable to describe to our students without using these essentialisms. It was not helpful.

I said I was going to present something positive so here it is. This is the progression model for RE that I have had in my head since my PGCE but which I’m only now confident enough to share.

Essentialism is … essential. I am a strong believer in the need to build up from core concepts as I wrote about in Seeds, Roots and Branches: a model of enquiry in RE. It’s natural for teachers to tie themselves up in knots finding ways in which the generally agreed upon key concepts are not, in fact, generally agreed upon. If we talk about the Trinity in Christianity someone will always bring up Unitarians. That may be true but there are only 7,000 Unitarians in the UK (0.02% of people who identify as Christian), so I would argue there is no need to add this confusion to a KS2 or even KS3 scheme of work.

Furthermore this essentialist stage is where we can lay some more groundwork in addition to theological concepts. We can introduce foundational stories, not just creation myths but stories that religions are built on like Buddha and the Four Sights or Passover or Abraham and Isaac. Of course interpretations differ but if we introduce them at KS1 and 2 we can talk about those differing interpretations at KS3, 4 and 5 without having to start from scratch. We can introduce specialist language that we will return to and we can talk about practices that are so widespread as to seem universal e.g. baptism, communion and prayer in Christianity.

Debate is a step beyond essentialism. It is still essentialising because that is what we do as teachers but it is introducing historical, long-standing or important debates. You cannot do this if you have not laid the groundwork above, I would say that is obvious but I have seen a lot of debate recently that suggests it might not be.

Once students understand the key concepts, practices and stories of a religion you can describe ways in which arguments have taken place over them throughout history. Most religions have a top tier division which has occurred at some point such as Orthodox and Reform Judaism, Sunni and Shia Islam, Theravada and Mahayana Buddhism, Catholic and Protestant Christianity etc. Now I can already hear some of you saying “what about Suffism? what about Pure Land? what about Orthodox?” and that is my gut reaction too but we are still essentialising in order to help simplify and build understanding so when those traditions are encountered they can be understood and investigated and not brushed over for the sake of diversity or completeness.

In addition to those historical splits you can look at contemporary debates both theological and in practices. This is where, in GCSE Christianity for example, we might look at liturgical vs non-liturgical worship or at literalist and non-literalist Biblical interpretations. We are starting to get to a richer and more true-to-life vision of religion by the time we reach the end of this point of progression. I have specifically designed this so that, if a student only studies RE until the end of KS3 or a core KS4 course they will still get to this debate stage. Though I’ve tied this section to upper KS3 and KS4 you can get here in Year 6 if you choose depth over breadth in your curriculum.

This section is probably not hugely dissimilar to Worldviews but it is reserved for upper KS4 and KS5 for a reason. At KS5 students can access complex debates and disagreements which add a rich and interesting dimension to studying religion but which, I would argue, are not essential for a general level of religious literacy.

Here we are talking about individual thinkers and theologians, we are talking about how an individual believer can deal with seemingly contradictory or difficult choices, we can talk about heresies and the challenges they’ve presented to religions and we can look at the unorthodox or unattached individuals and denominations that develop from those beliefs like Mormonism or Kabbalah.

Meanwhile this all builds on, enriches and links into the work done in the essentialism and debate stages of this model. Not every student is going to reach the diversity stage of the model but those that do are most likely to continue to further study whether in Theology, Religious Studies or another related degree. Some people will be asking why this diversity stage can’t be taught simultaneously alongside KS3 or KS4. That is when it becomes tokenistic. To introduce Arianism to a KS3 scheme of work on Jesus seems like a noble venture but will never allow a student to understand fully the historical or theological context for Arianism or the effects of that heresy on the Church following it. Additionally a working knowledge of Arianism is probably not needed for even a high level of religious literacy.